Over the years, the IceCube Neutrino Observatory at the South Pole has collected an abundant amount of muons and neutrinos produced in the Earth’s atmosphere. These neutrinos are produced when high-energy particles called cosmic rays collide with atoms in the Earth’s atmosphere and produce “air showers” that rain down on Earth. Previous studies showed that the neutrino detection rate varied with an “effective temperature” in the stratosphere above Antarctica, suggesting a connection between seasonal changes in the upper atmosphere and the number of neutrinos that are detected.

In a paper submitted to The European Physical Journal C, the IceCube Collaboration looked at the dependence of neutrino energy on seasonal variations by comparing IceCube data to existing atmospheric models. The analysis showed agreement between the data and existing models, proving that IceCube can be used not only for astrophysical observations but also for studying atmospheric processes over Antarctica.

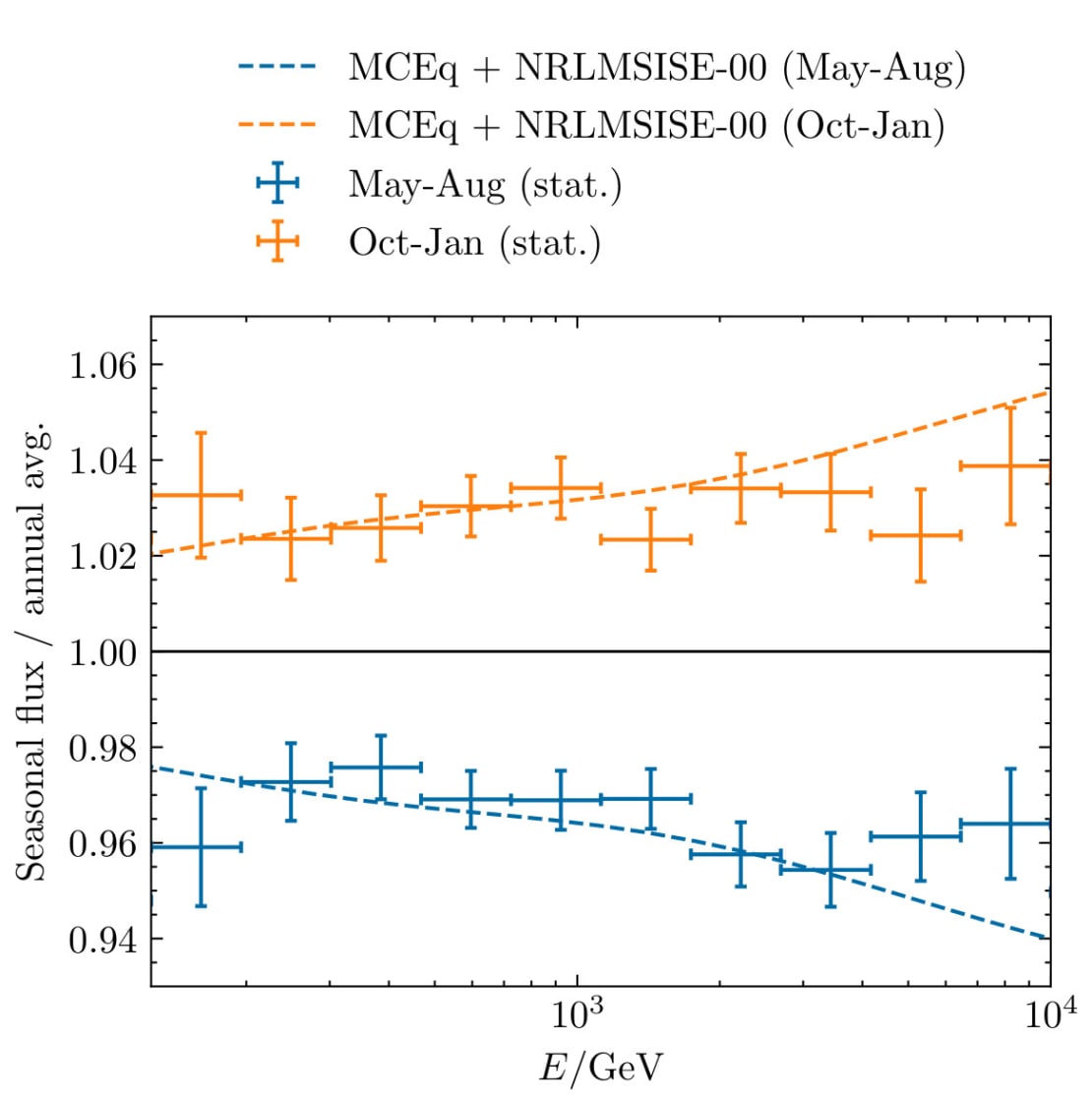

Researchers used 11 years of IceCube data for the analysis, which doubled the size of the dataset used in a previous IceCube study on seasonal variations. They applied machine-learning techniques to estimate the energy spectrum of atmospheric muon neutrinos based on the signals recorded by IceCube. The researchers accounted for given uncertainties, such as how the sensors are calibrated and how light travels through the Antarctic ice, by comparing the neutrino energy distributions measured during different seasons with a year-round average. This enabled them to achieve high precision over a wide energy range—from a few hundred GeV up to roughly 10 TeV.

What the researchers observed was a clear seasonal pattern: more neutrinos were arriving during the warmer Antarctic summer than during the colder Antarctic winter. This effect became stronger at higher energies and matched theoretical models that link atmospheric density changes to neutrino production.

“It confirms that we are correctly accounting for seasonal variations when searching for astrophysical neutrinos,” says Karolin Hymon, a recent PhD graduate from TU Dortmund University in Germany, now a postdoc at the Institute of Physics, Academia Sinica, Taiwan, who led the study. “It also opens up exciting possibilities for using these natural atmospheric density changes to refine our understanding of particle physics—especially how cosmic rays interact and produce neutrinos.”

With the completion of the IceCube Upgrade and expansion of IceCube, IceCube-Gen2, researchers will be able to “tighten constraints on atmospheric flux models, reduce uncertainties in fundamental neutrino property measurements, and enhance overall understanding of cosmic ray interactions.”

+ info “Seasonal Variations of the Atmospheric Muon Neutrino Spectrum measured with IceCube,” IceCube Collaboration: R. Abbasi et al. Submitted to The European Physical Journal C. arxiv.org/abs/2502.17890