Last year, the “Name that Neutrino” project was launched, which called on volunteers from the public to help classify signals from neutrinos—tiny, ghostlike particles—for the IceCube Neutrino Observatory at the South Pole. The project was hosted on Zooniverse, the largest web-based research platform that invites novices and science enthusiasts alike to contribute to ongoing research through an online experience.

Over the course of six months, 1,800 registered Zooniverse users aided in 128,000 classifications of IceCube neutrino events, demonstrating the power of citizen science. The findings were reported in a study recently submitted to a European Physical Journal Plus focus issue on citizen science for physics.

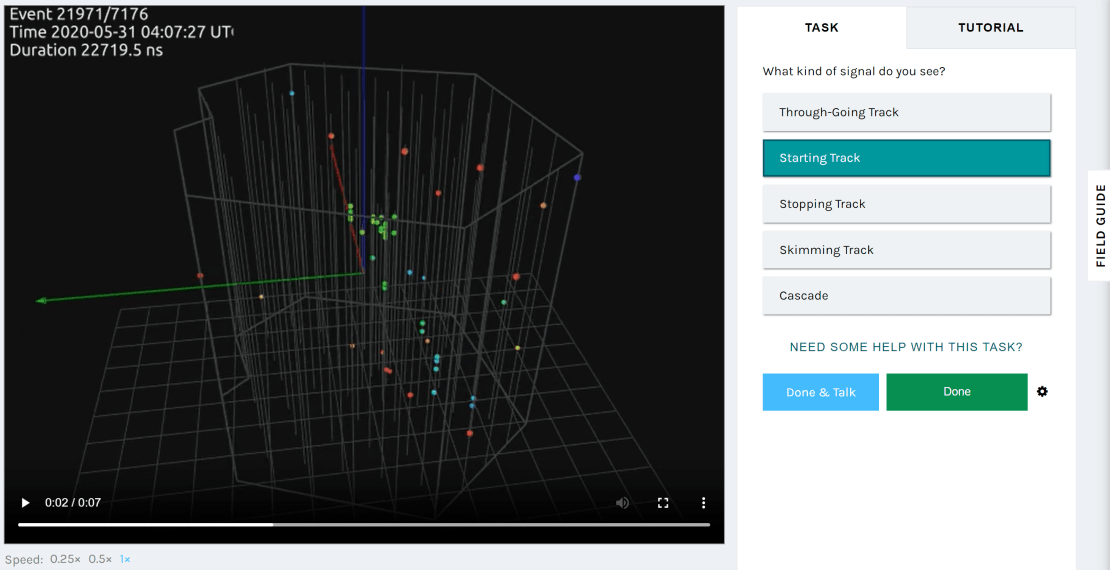

“Name that Neutrino,” asked volunteers to recognize light patterns created from secondary charged particles in order to aid in reconstructing the neutrino’s energy and direction. Prior to requesting the public’s help, IceCube had already developed a deep neural network (DNN) machine-learning algorithm to help classify neutrino events into one of five topologies: through-going track, starting track, stopping track, skimming track, and cascade. But even with advances in machine learning, some things remain difficult for computers to identify.

For the project, the collaborators compared the performances of both the citizen scientists and artificial intelligence.

All in all, there was some agreement between classifications done by the human eye and the DNN machine-learning algorithm.

“This initial study has demonstrated the feasibility of using the citizen science approach to classify IceCube data,” says Associate Teaching Professor of Physics Christina Love of Drexel University, a lead on the project. Elizabeth Warrick also contributed to the project as a physics master’s student at Drexel University.

Love and collaborators are already working on the next stage of “Name that Neutrino,” which will offer cleaner neutrino events, improved user tutorials, and a lot more videos to capitalize on a successful first attempt by IceCube in engaging the public in research.

+ info “Citizen Science for IceCube: Name that Neutrino,” IceCube Collaboration: R. Abbasi et al., The European Physical Journal Plus 139, 533 (2024), link.springer.com, arXiv