The interior of Katherine Rawlins’s Cessna 172 airplane, “Becky,” is similar to the interior of a car. There are two seats in front and two in back; the back two fold up to allow for more storage, which Rawlins happily takes advantage of. “I have a big bag of survival gear, like cooking equipment and fishing gear and signal flares and a hatchet and water purification and all kinds of things I would need if I were to crash in the wilderness,” says the University of Alaska Anchorage physics professor and IceCube collaborator. She also has snacks, technology needed to get work done, and a years’ worth of clothing for every season.

Rawlins has to be prepared for anything because Becky is her main mode of transportation for the next six months. In fact, since August 2019, the physicist has been flying her sturdy 1972 airplane around the continental United States to visit collaborators and conduct research. It’s how Rawlins has chosen to spend her sabbatical year.

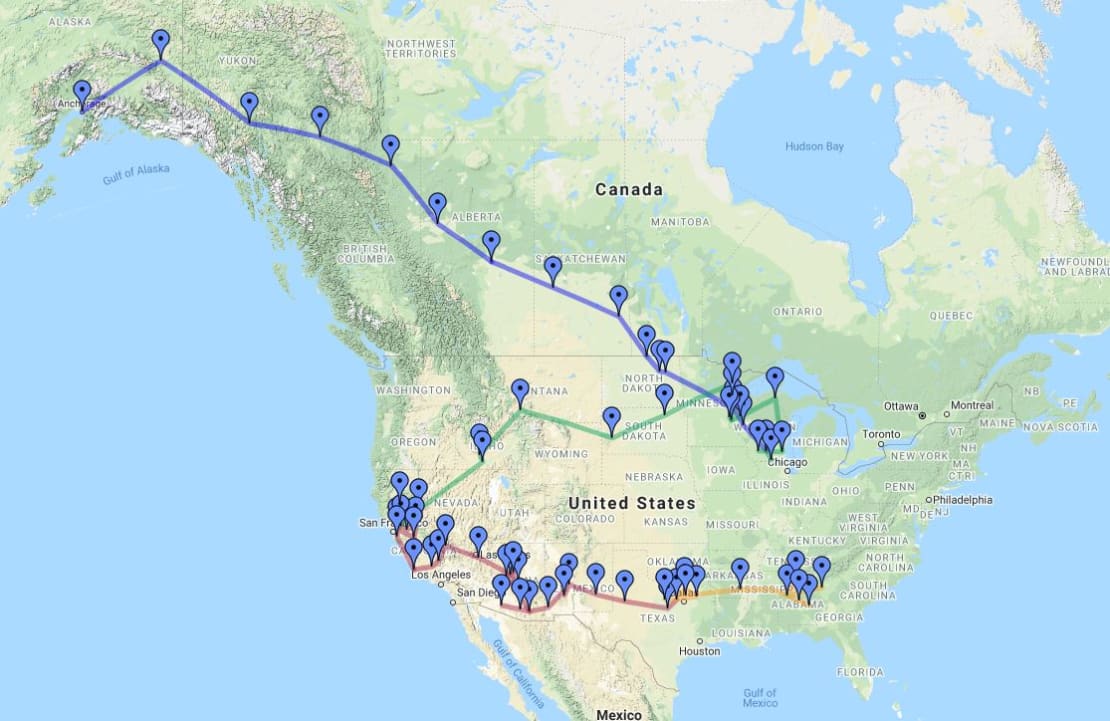

Her first destination back in August was Madison, Wisconsin, to visit the place where she earned her physics PhD while working on the early stages of the IceCube project: the University of Wisconsin–Madison. Since then, Rawlins has flown through and stopped in Minnesota, South Dakota, Montana, Idaho, Nevada, California, Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, and Alabama. She even took a few days to go to a conference in Sydney, Australia (albeit not with Becky). Now she is in Atlanta, Georgia, where she will stay for a few days before heading to Florida.

How did this physicist get her wings? It turns out that IceCube played a role in helping Rawlins achieve her dream of flight.

Rawlins had wanted to take to the skies since she was a young girl. “I was one of those kids who wanted to be an astronaut when I grew up,” she says. “I had pictures of the space shuttle on my wall, and I was into airplanes and flying from a very, very early age.”

That dream stayed with Rawlins into adulthood. But learning to fly is an expensive hobby, so she had to save up funds. The perfect opportunity came in 2001 when, after earning her physics PhD, she went to the South Pole as a winterover for the AMANDA experiment, a precursor to IceCube. For an entire year, Rawlins lived at the South Pole, keeping the experiment running and fixing any problems that arose.

Conveniently, winterovers don’t need to pay for food, housing, electricity, or most other expenses of daily life, so their salary just adds up. “Everybody makes different plans for what they’re going to do with that nest egg when they get back,” says Rawlins. “Some people say, ‘Oh, I’m going to pay off my house or buy a piece of land.’ I said, ‘I’m going to blow it all on flying lessons.'”

So when she got back from the South Pole and began a postdoctoral position at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Rawlins found a place to start: Hanscom Field in Bedford, Massachusetts, an airport on the outskirts of Boston.

In order to not interfere with her postdoc work, Rawlins would sneak in an hour or two of flight training in early mornings and on weekends, once or twice a week, weather permitting. To make things even more challenging, Rawlins didn’t have a car. “That particular airport was the one that I could get to by public transportation, if necessary, or by bike,” she says. “So I would get up at 5:30 in the morning so that I could ride my bike out to Bedford airport and be there as soon as the flight school opened. Even in the winter when it would be 10 degrees, I’d show up on my bike, all bundled up. The people at the flight school thought I was crazy.”

Nine months of lessons later, Rawlins had earned her private pilot certificate, which allowed her to fly around with friends and family. She would rent an airplane from Hanscom Field and fly people to local destinations like Martha’s Vineyard, Nantucket, and Portland, Maine. (She couldn’t stay away from Madison for long; she once rented a plane for 10 days to fly back to her “home away from home.”)

In 2005, Rawlins accepted a position at the University of Alaska Anchorage. There, she found a place to rent an airplane and get even more training. That’s also where she met her husband—a fellow pilot and airplane owner.

Rawlins has now lived in Anchorage for nearly 15 years. Her most recent flight achievement was earning her flight instructor certificate in the summer of 2018. She has since trained a student and hopes to teach more once she’s back in Anchorage.

What’s the appeal of flying? “It’s very focusing,” says Rawlins. Since her days as a PhD student, Rawlins has found refuge in tasks that require lots of sustained attention, like sailing with UW–Madison’s Hoofers Sailing Club.

“Back then, that was my escape from the rigors and stresses of life, to go take a sailboat out on the lake,” recalls Rawlins. “You don’t think about work when you’re out on the lake. You just think about the wind and the sail and you’re always making little adjustments and watching everything and…the boat becomes your little world and everything else fades away.

“Flying is really similar. Everything in this cockpit is your little world that you can control, and all the other worries and stresses of life are left behind. You have to focus on what you’re doing. And that’s one of the things I like about it. Flying is like sailing in three dimensions.”

While in the air, Rawlins can’t move around the cockpit, but like on a road trip, she can still reach for snacks and water from the “shotgun” seat during flight. She usually doesn’t listen to music while in the air; if possible, she stays tuned into the local air traffic control radio. And although the plane can fly for five hours on a tank of gas, Rawlins prefers to “pull over” (i.e., land) for fuel whenever the tank is more than halfway empty.

Still, operating a small plane is undeniably risky. Safety-wise, it’s more akin to driving a motorcycle than driving a car. So Rawlins doesn’t take chances. “I have to be flexible on a trip like this because the weather will determine where and when I can fly,” explains Rawlins. “I try to be a safety-conscious and cautious pilot who does not mess with bad weather.”

Six months into her adventure, Rawlins has had a safe trip, suffering no more than a blown tire on a runway in Concord, California. She’s also seen quite a few exciting sights so far, both for fun and for science. She’s lent a hand with deployment of the CHIPS detector in northern Minnesota and has visited the Homestake mine (now SURF) in South Dakota, the Whipple Observatory in Arizona (including telescopes for the VERITAS and CTA projects), and the Very Large Array in New Mexico. She has spent research time at six different IceCube institutions (see photos below), with many more still to come.

Next, Rawlins plans on visiting Georgia and Florida before making her way up the east coast in the spring, flying back to the Midwest in the summer, and returning home to Anchorage in August 2020.

So far, Rawlins says she’s been overwhelmed by the hospitality she’s received, from friends, colleagues, and even total strangers. “I’ve gotten to reconnect with people I haven’t seen in years as well as make new friends in the physics community. And see the country in a new way, and visit places I’ve never been and might not normally go.”

Blue skies and tailwinds, Kath!