Once or twice per day, a muon neutrino interacts with a molecule of ice near one of the 5,000 sensors of the IceCube Neutrino Observatory. This weak interaction mediated by W boson is what scientists call a charged-current interaction, which produces a hadronic shower and a muon. The muon travels across the detector in a straight line, following almost the same direction as the original neutrino.

This hadronic shower carries a fraction of the energy of the original neutrino, a parameter known as inelasticity. A better understanding of the inelasticity of neutrino interactions provides another way of deepening our knowledge of the unique physics hiding behind ghostly neutrinos.

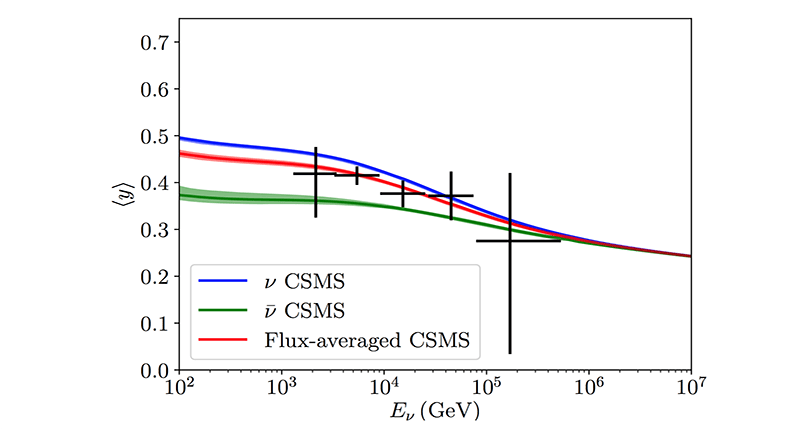

The IceCube Collaboration has recently presented its first measurements of the neutrino inelasticity, which are also the first-ever at very high energies—from 1 TeV up to nearly 800 TeV. The inelasticity distribution was found to be in good agreement with Standard Model prediction and was later used to perform other measurements, such as charm production in neutrino interactions or flavor composition of astrophysical neutrinos.

These measurements are summarized in a paper recently submitted to Physical Review D and, together with previous measurements of the neutrino cross section, show the potential of astrophysical and atmospheric neutrinos as a tool for particle and nuclear physics at high energies.

Scientists analyzed five years of IceCube data looking for starting multi-TeV neutrino interactions and found 2,650 tracks and 965 cascades. These tracks are mostly charged-current muon neutrino interactions for which the energy and inelasticity were measured.

“The measurement of inelasticity was made possible with concepts from machine learning. Using thousands of simulated neutrino interactions, we were able to train a computer algorithm to learn the energy of the hadronic shower and the muon from the complicated pattern of light detected by IceCube’s sensors,” explains Gary Binder, who worked on this analysis during his PhD at the University of California, Berkeley.

Neutrino inelasticity depends on the momentum distribution of quarks and antiquarks within nuclei. For example, the production of charm quarks is sensitive to the number of strange sea quarks in the nucleus. And a fit to IceCube data revealed charm quark production with more than 90% confidence.

On the other hand, the inelasticity distributions for neutrinos and antineutrinos are somewhat different, and IceCube data allows to measure the ratio of antineutrinos to neutrinos produced in cosmic-ray air showers.

“This analysis shows that IceCube can make significant contributions to the study of neutrino interactions, probing energies that are far beyond those accessible with terrestrial accelerators,” explains Spencer Klein, an IceCube researcher at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and at University of California, Berkeley, and a coauthor of this work.

This first measurement of the neutrino inelasticity at high energies also proved to be useful for studies of the astrophysical neutrino flux. The inclusion of inelasticity in an otherwise standard IceCube fit provides tighter constraints on the flavor composition of astrophysical neutrinos.

This study developed a new approach to reconstructing starting tracks. It measured, separately, the energy of the cascade produced by the neutrino interaction and the muon that emerged from it. The sum gives the total energy, and the ratio of the cascade energy to the total energy is the inelasticity. The new technique produces a far more accurate energy estimate for starting tracks, which can be used to better probe the astrophysical neutrino energy spectrum––the current study found that starting tracks are consistent with other IceCube measurements.

These results confirm that large-scale neutrino detectors can measure the inelasticity distribution of high-energy neutrinos, but the cubic-kilometer Antarctic detector has not yet reached the sensitivity that will enable precision tests of the neutrino sector and thus rigorous searches for new physics. Looking ahead, the inclusion of inelasticity in future IceCube starting event analyses will further tighten the constraints on the presence of tau neutrinos. More generally, inelasticity measurements are now known to be a robust tool for future, larger neutrino telescopes, such as the ten-cubic kilometer IceCube-Gen2 or the Mediterranean neutrino detector KM3NeT.

+ info “Measurements using the inelasticity distribution of multi-TeV neutrino interactions in IceCube,” IceCube Collaboration: M. G. Aartsen et al., Physical Review D 99, 032004 (2019), journals.aps.org, arxiv.org/abs/1808.07629

+ Gary Binder receives GNN Dissertation Prize 2018, learn more here